Here you will find a selection of tableaux, sculptures, and installation work. I’m including the process and research of working up to the finished pieces too, as this is just as important as the completed work.

Digging deep into a subject, allows that research to inform and shape the finished piece, giving narrative to the work.

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

Blinded By The View

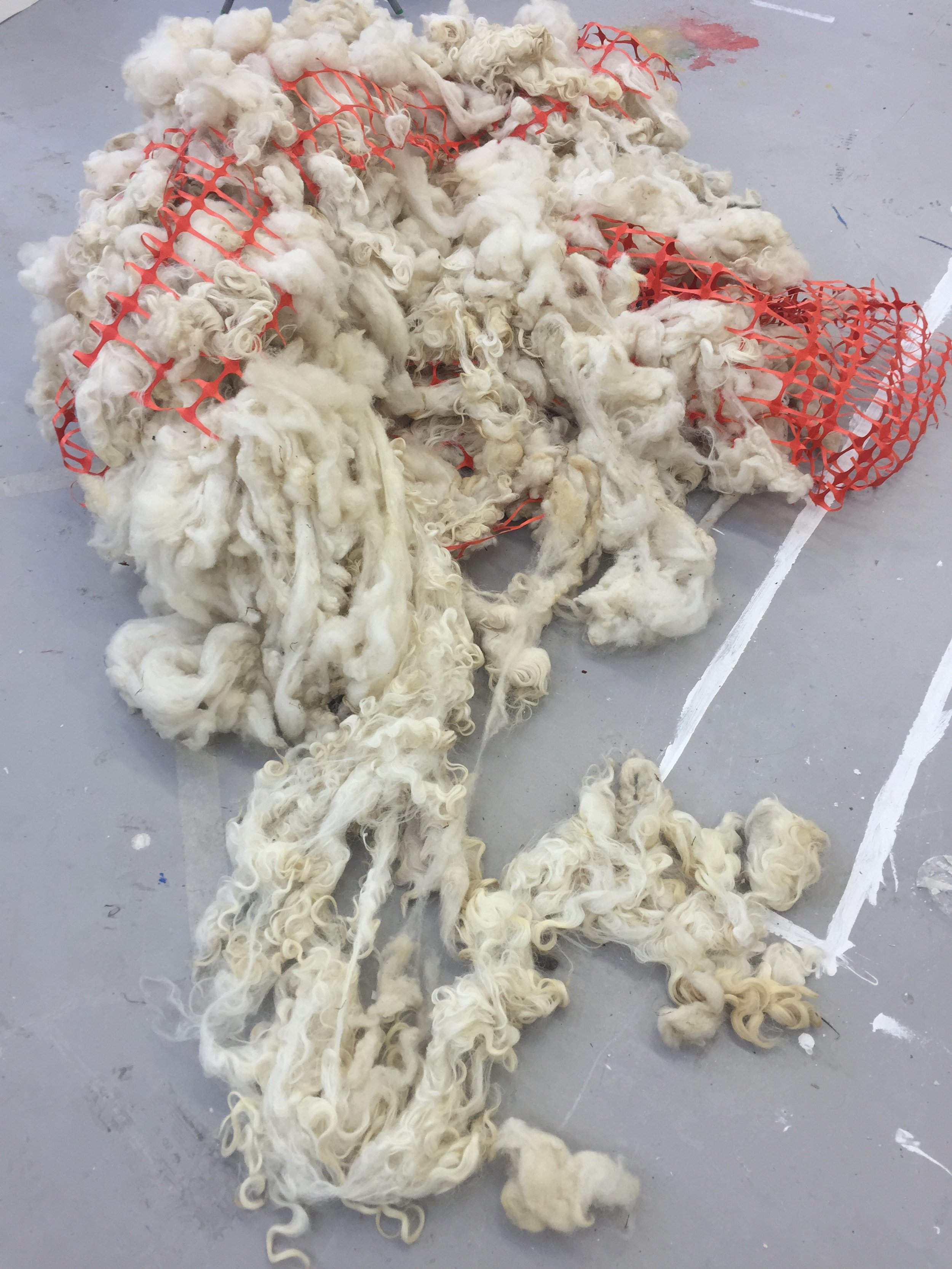

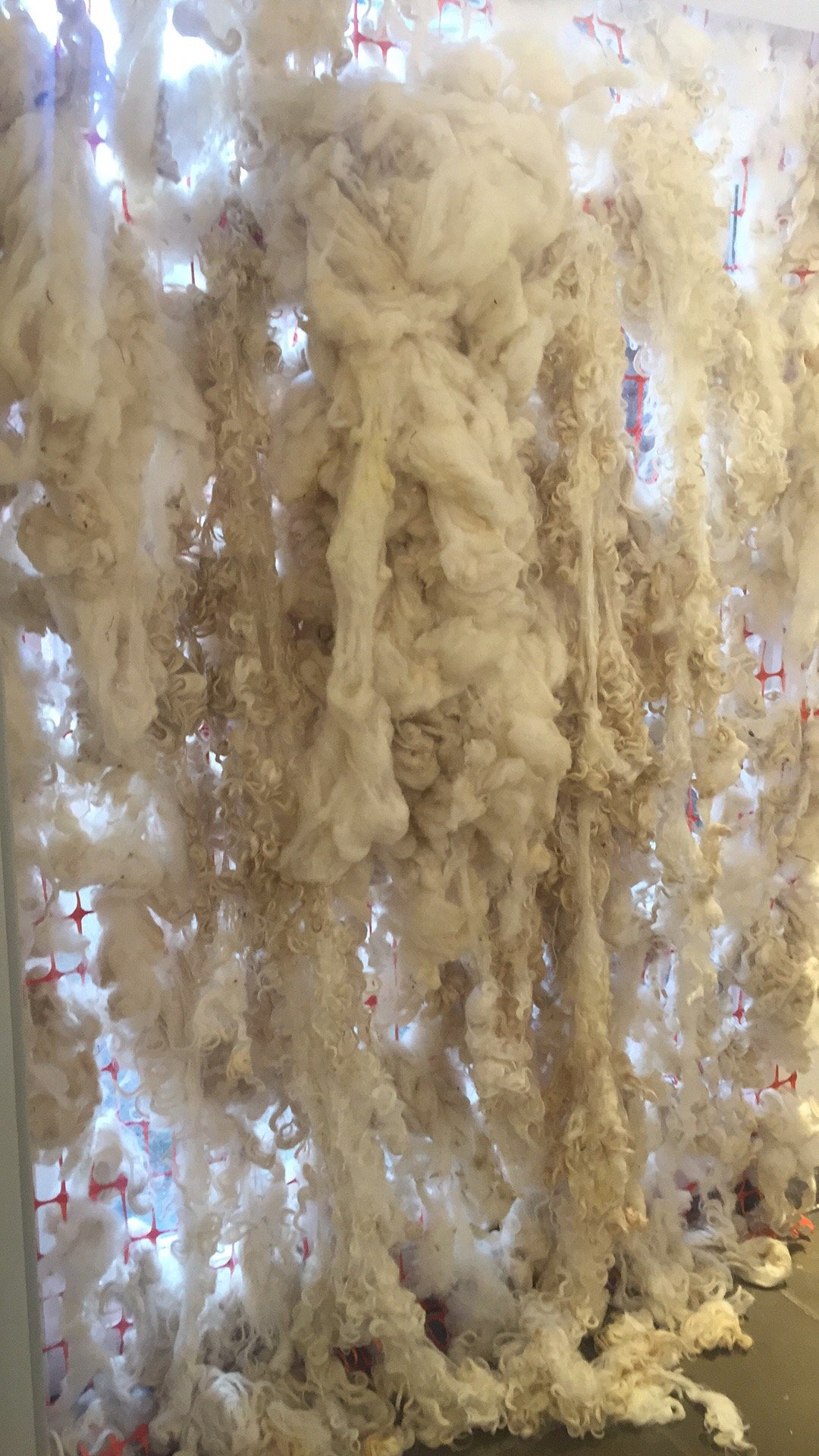

This artwork was created for the Gustav Metzgar collaborative exhibition on Nature. The piece was a labour intensive. I utilized the builder’s mesh as a base and metafore to the building industry. The four sheep fleeces were meticulously cleaned, by picking out all the dirt, and then hand-washing them outside in an old tub, they needed several washes and rinses. The water used was repurposed to water the garden. The fleece was hung on a washing line to dry out in the sun, and then after a few test pieces, it was decided to hand weave the fleece into the mesh in situ.

It serves as a commentary on the encroachment of natural landscapes by developers and government-led housing projects, highlighting the impact of construction on the environment.

...We forget that battlefields are one kind of landscape and that most landscapes are also territories...on a small scale, they involve...a sense of place, on a large scale they involve war.... (the landscape is) not just where we picnic but where we live and die...Rebecca Solnit, As Eve Said to the Serpent: On Landscape, Gender, and Art, 2001

To Solnit the “landscape” gives rise to the social, political, and philosophical landscapes we inhabit, and it is this direction this work takes, looking at the interrelationships between nature and culture.

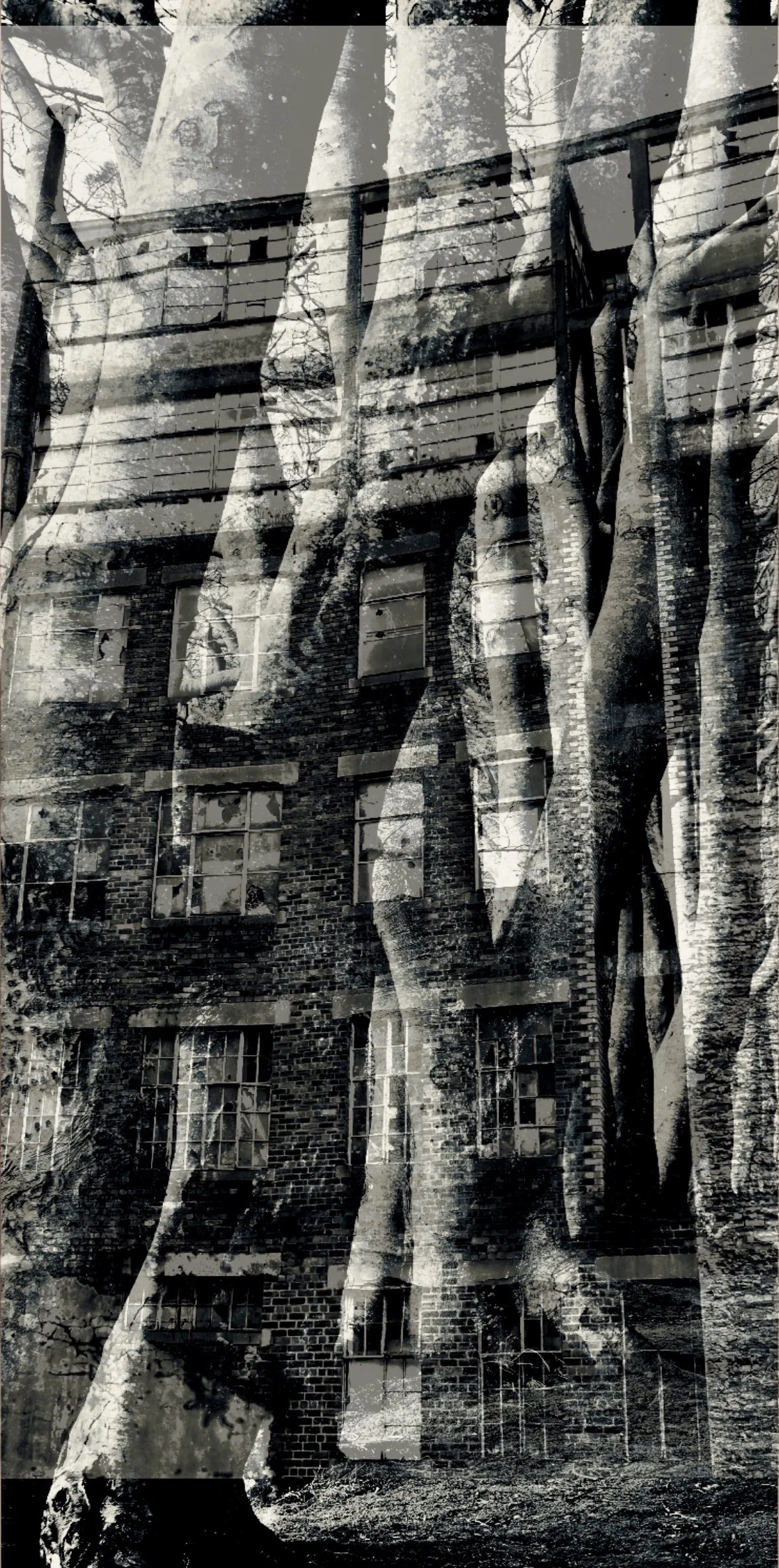

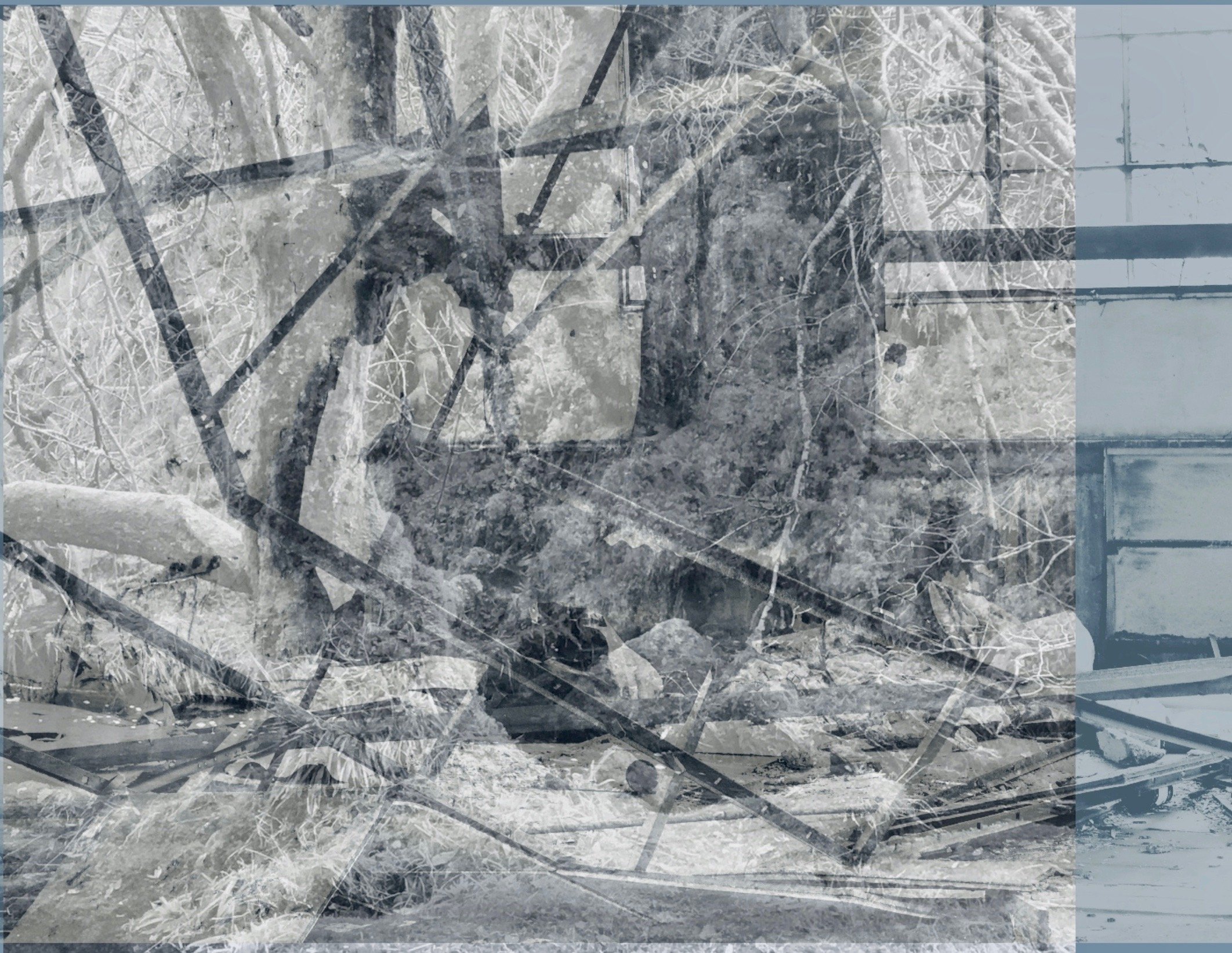

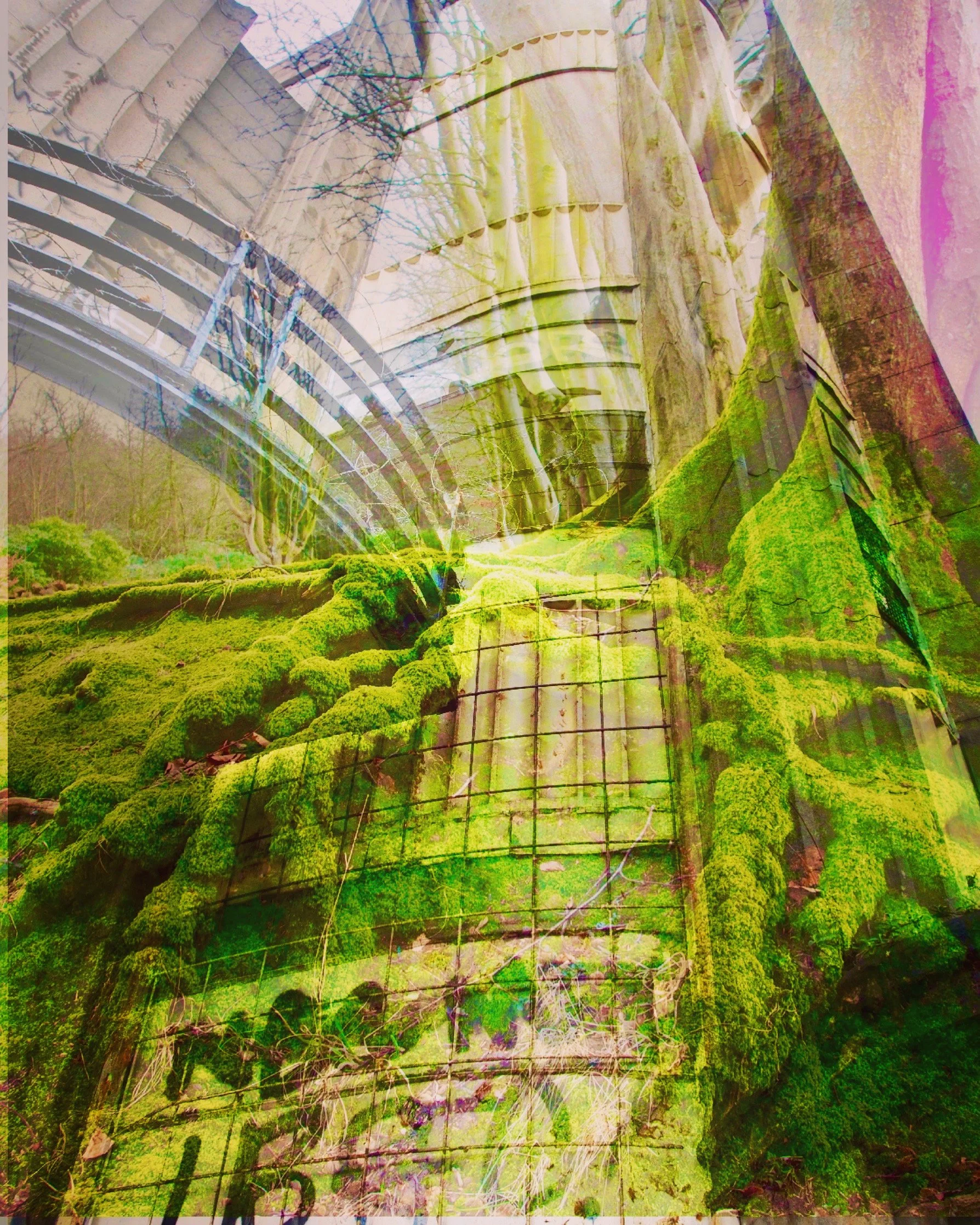

This work stems from my time in Glasgow and its surrounding decaying industrial landscape, what could be seen as decay and memory within, layers and layers of stories, broken down and forgotten. Mixed with the progress of technology.

Post-Landscape as Activism: Rewriting the Visual Politics of the Environment

My concept of the “Post-Landscape” proposes a new mode of engaging with environmental imagery, one that refuses the passivity associated with the picturesque or the sublime. Instead, Post-Landscape operates as a critical space where the viewer confronts the constructed-ness of the environment and the ideologies embedded within it. By blending installation, photography, and painting, My practice destabilises traditional landscape conventions and encourages viewers to recognise the socio-political forces that shape the land: industrial heritage, ecological degradation, gendered symbolism, and the language of ownership. This reconfiguration is inherently activist because it challenges entrenched visual traditions that have historically silenced both ecological concerns and marginalised identities. My work insists that to rethink landscape is to rethink our relationships to land, gender, and power. In doing so, it transforms the act of viewing into a conscious engagement, a call to recognise and resist the structures that attempt to naturalise inequality, whether environmental or social.

Nature, Ecology, and the Gendered Politics of the Landscape

My work’s engagement with ecology and land use highlights the ways in which landscapes have long been subjected to systems of control, whether through enclosure, industrialisation, or the scientific impulse to categorise and dominate the natural world. At the same time, culture has historically feminized nature, casting it as passive, fertile, emotional, or chaotic, qualities patriarchal societies then project onto women themselves. By foregrounding stereotypes of women within natural spaces and connecting them to ecological concerns, I show how environmental exploitation and gender oppression stem from the same logic: a worldview that positions dominance as progress and control as necessary. Situating the feminine body metaphorically within damaged or threatened ecosystems brings visibility to this shared vulnerability. It also reframes ecology not as an abstract scientific topic but as a lived social reality. The ecological crisis becomes inseparable from a crisis of language, representation, and social power, something your work actively surfaces.

This Broken Land

Photomontage as a Critical Tool for Reframing Nature and Culture

By employing photography and photomontage, My work intervenes in the historical ways landscapes have been visually constructed and consumed. Photomontage in particular disrupts the seamless, “naturalised” representation of the landscape that traditional painting or photography often reinforces. Instead of offering a passive view of nature, the collage forces ruptures, overlays, and confrontations between human-made objects, ruins, and organic forms. These interventions expose the cultural frameworks that shape how landscapes are read, frameworks rooted in colonialism, industrial expansion, and gendered assumptions about who belongs in nature and who gets to represent it. Through this medium, I reveal that the landscape is not a neutral backdrop but a site encoded with power relations. Photomontage becomes a methodological form of activism because it visually “breaks apart” inherited narratives, pushing the viewer to question their internalised ideas about purity, wilderness, and the supposed separation between nature and culture.

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

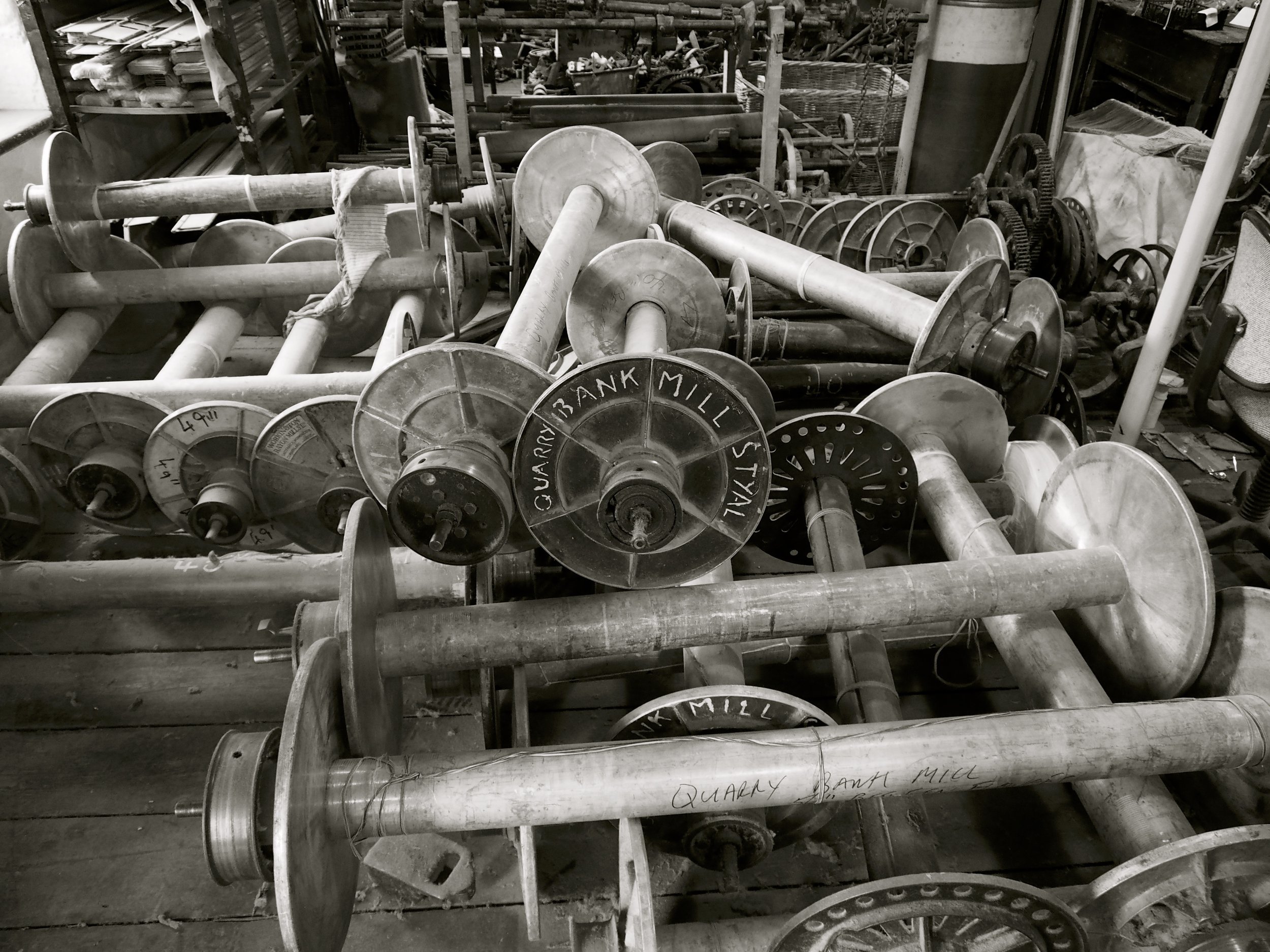

“Trade” and “Mee Maw”

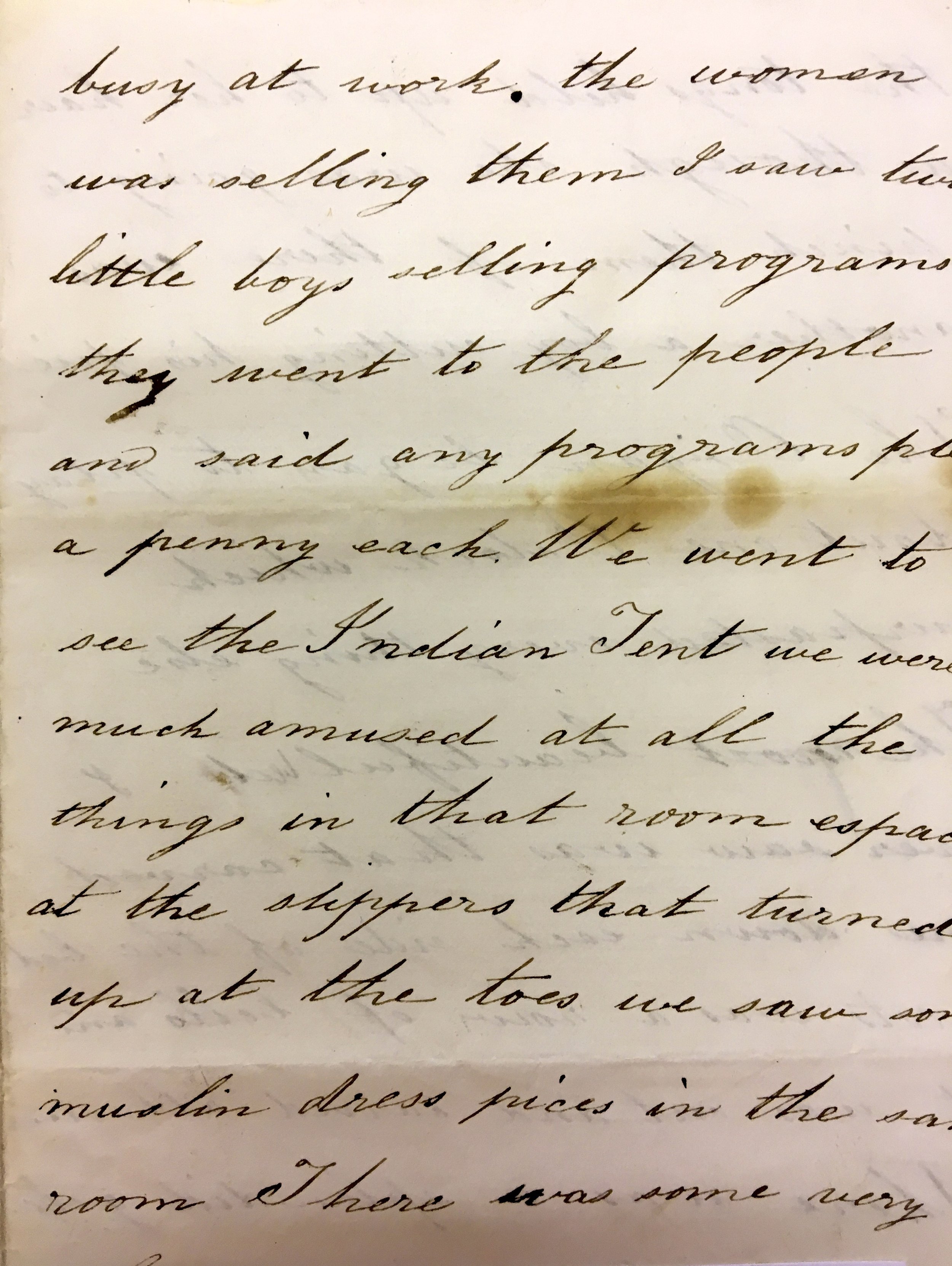

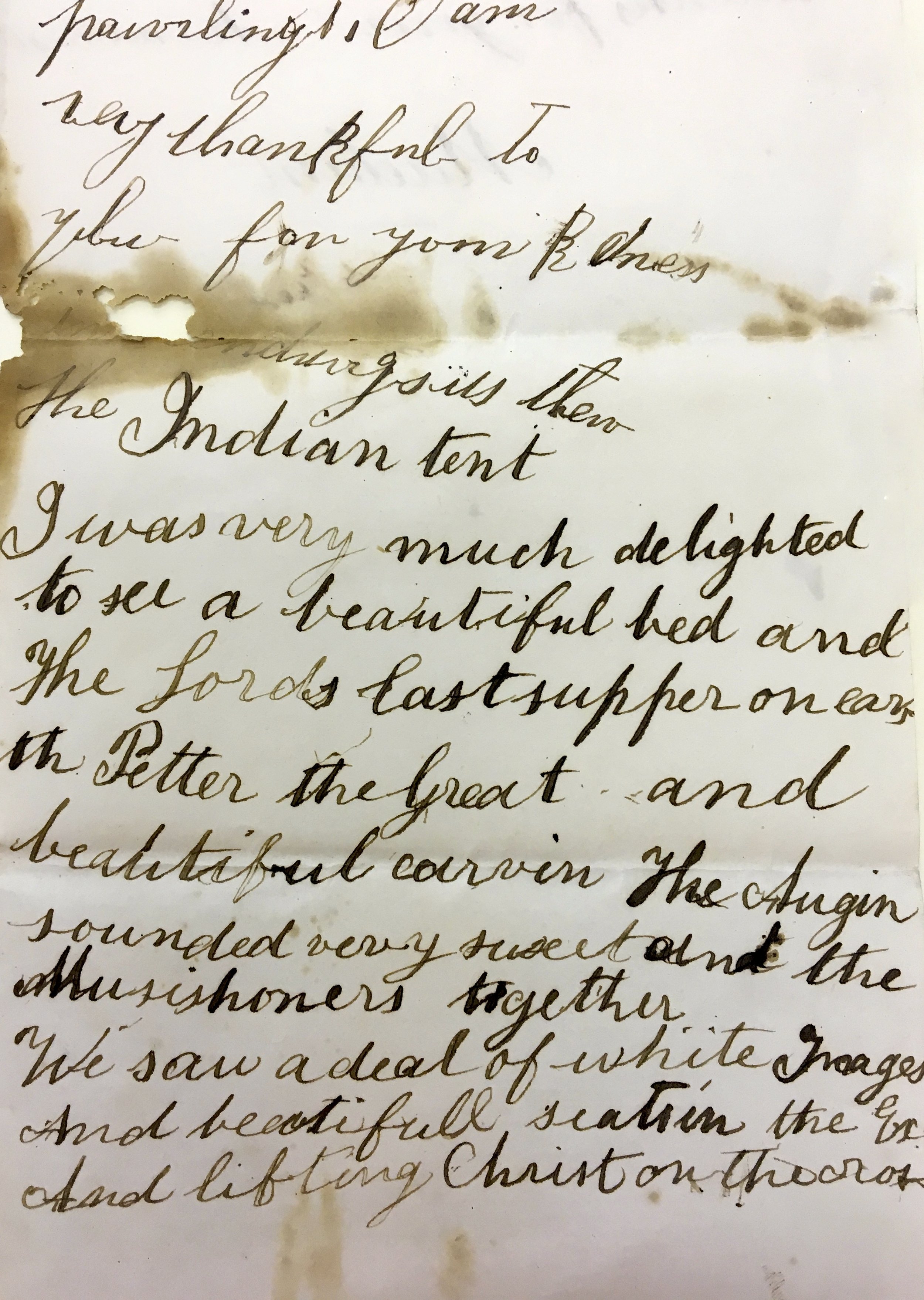

This work is a research series that spans both women and industry, created after a long period of research in the archives of Quarry Bank Mill, and Tameside Library tape recordings, of the ladies who used to work in the Cotton Mills and speak to local people and my own family from the era of the mills.

These paper patterns represent the body, and women in the Mills that worked for next to nothing, they form another layer of narrative, a skin, Ghostly presence of a woman’s clothing patterns but also an absence or loss. The Mee Maw film was a form of communication while the ladies worked in the Mills, as it was dangerous to speak when the bosses were around.

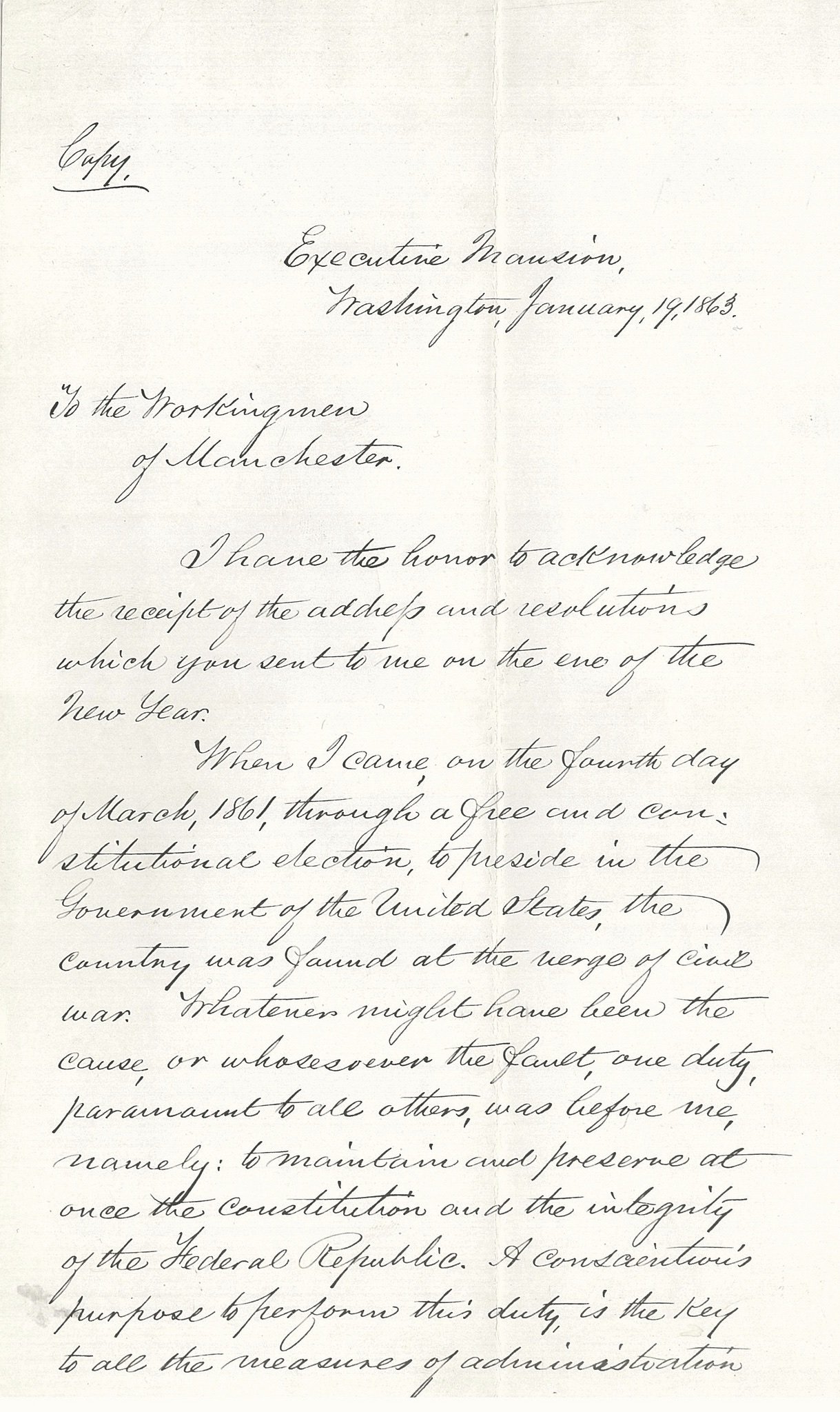

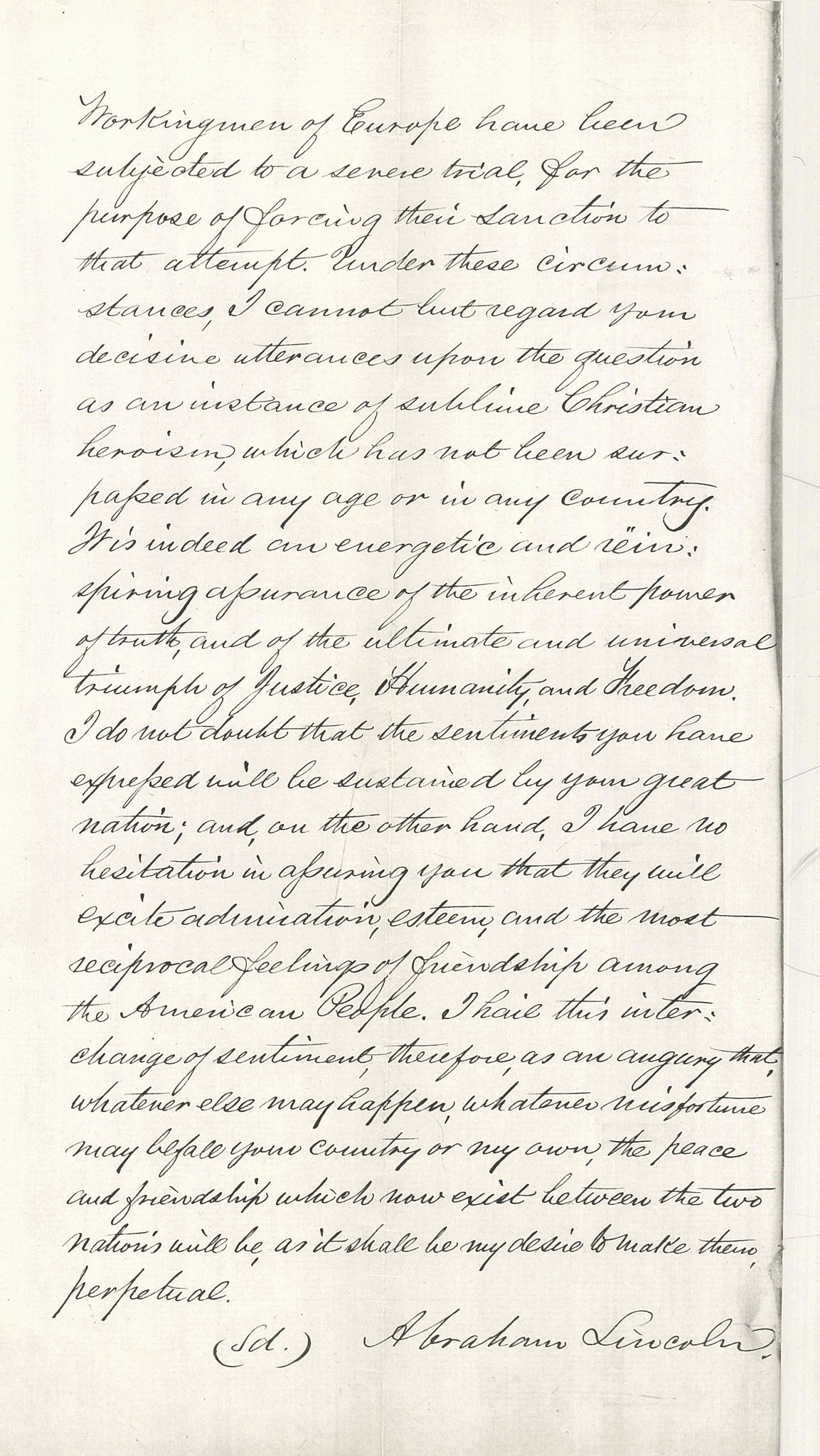

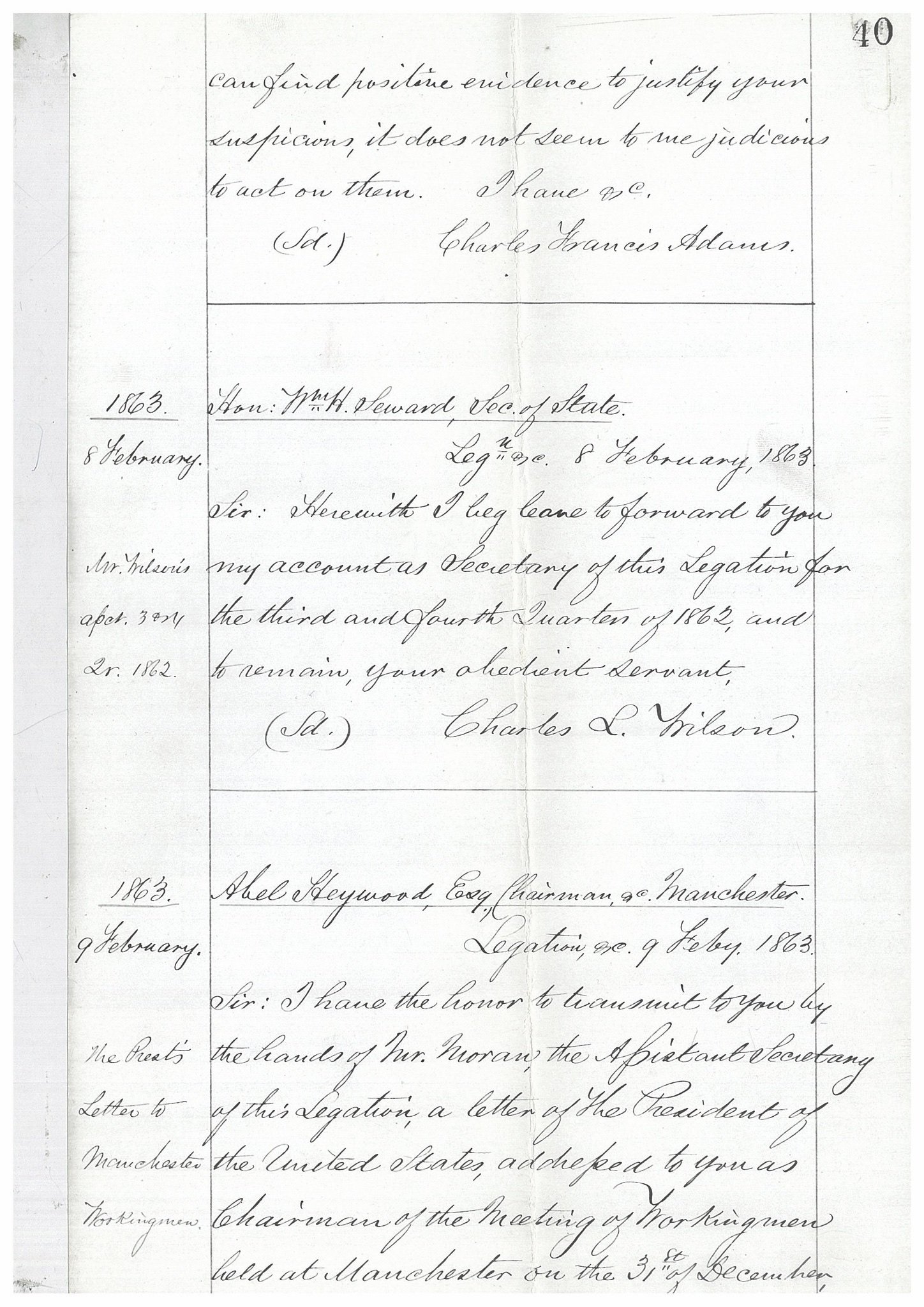

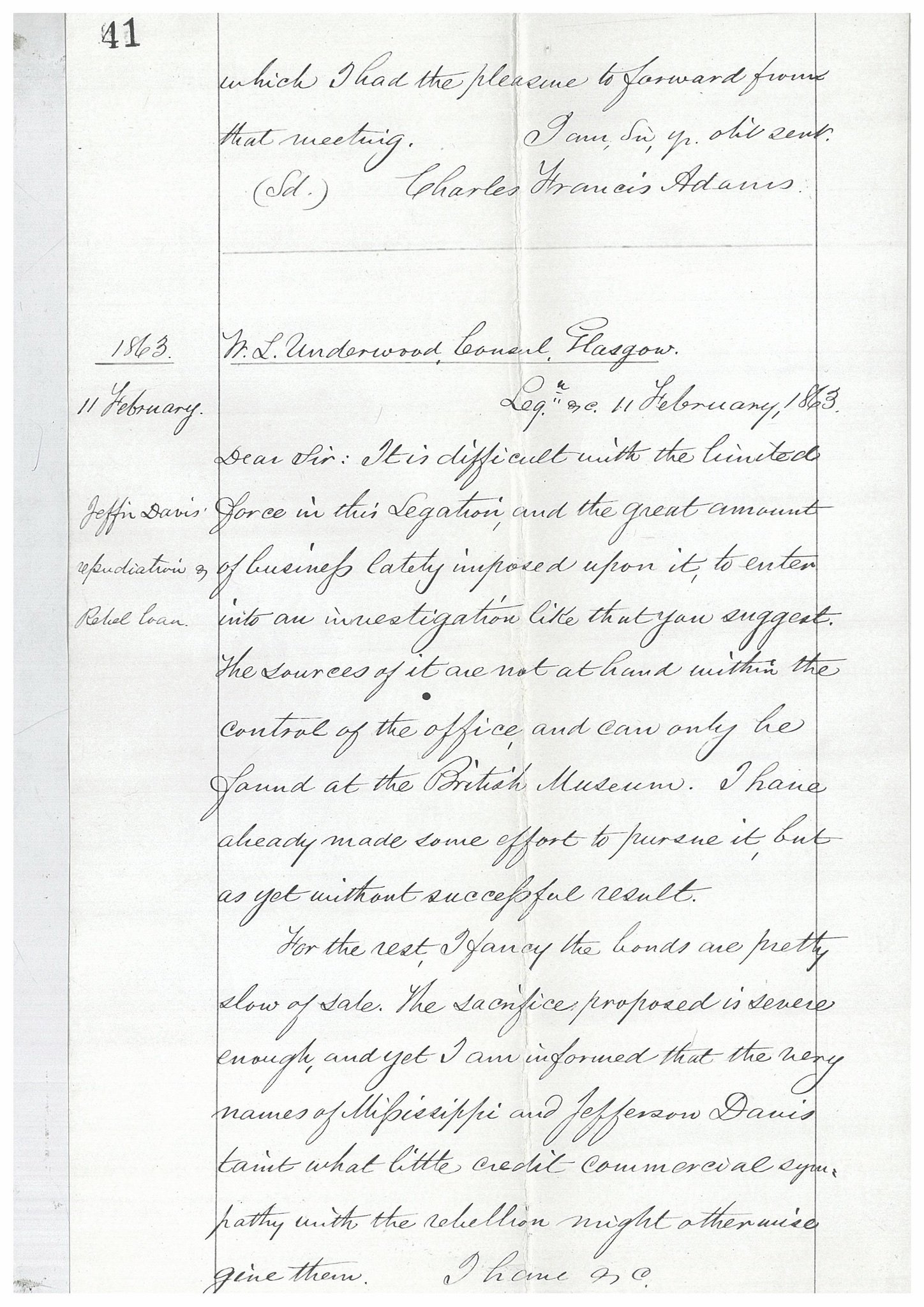

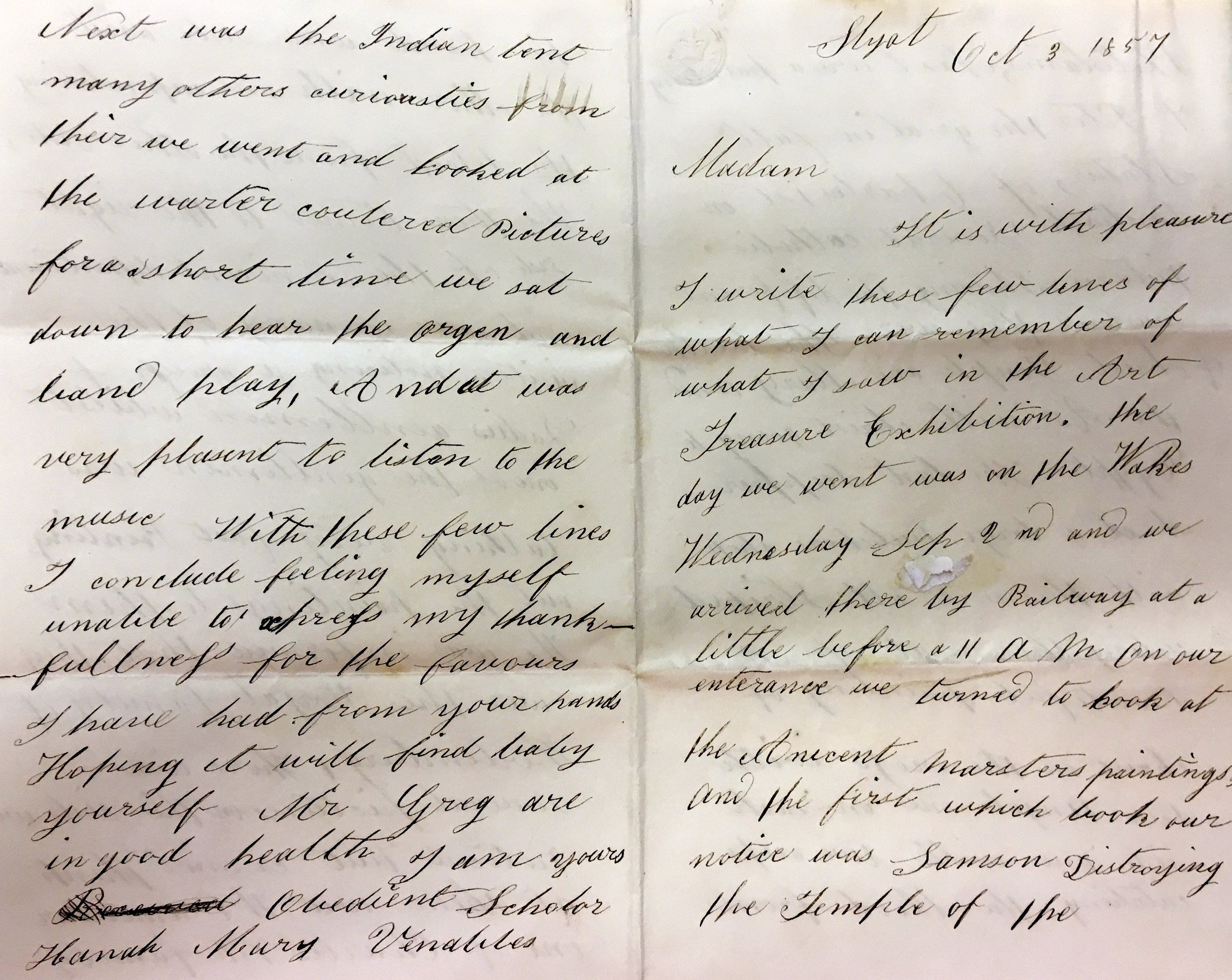

During my research into the Mills and life of the working women and children in Quarry Bank Mill and other Mills around the North West and Manchester, I found letters from mill workers to families, and a letter addressed to the people of Manchester for Abraham Lincoln.

Walter Benjamin wrote, “For every image of the past that is not recognised by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably”. History and its fragments stand as memories within the human mind, it is only when we confront fragments that memory is awakened, creating a surreal moment of connection with the artwork, object and audience.

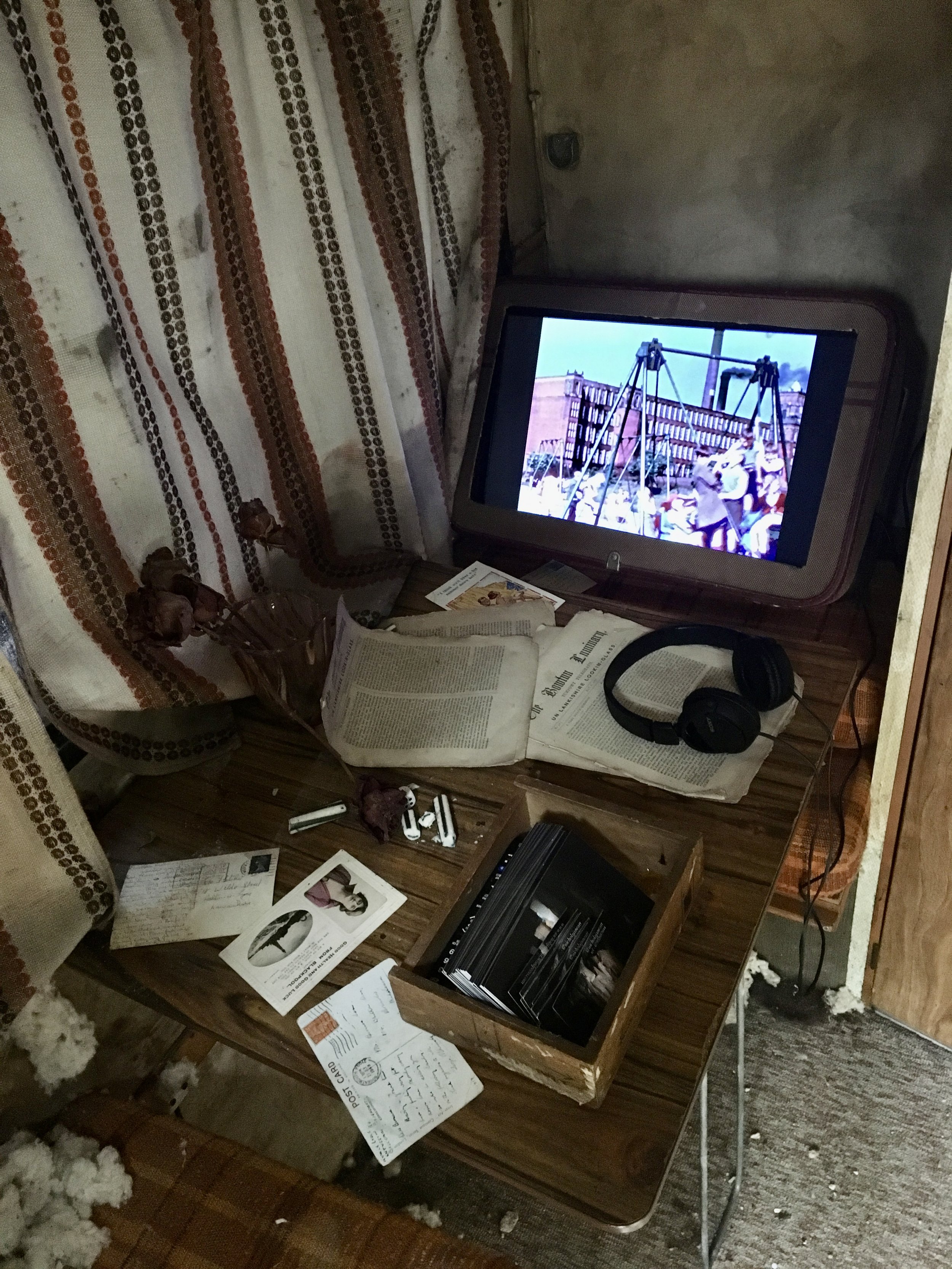

This installation was created as a follow-on from the previous research into the North West, its industry and traditions.

The caravan is mourning the loss of both industry and our connections with the working class of Britain.

The working class are the people that built Britain, and put the Great into Great Britain, through hard labour. These are also the people who prided themselves as honest working people who stood up for the abolition of slavery in America and refused to work with slave-traded cotton in 1863, causing the cotton panic.

During the working year, many of the cotton workers only got one day off work a year, this did increase but the holidays stayed the same for decades to come - The caravan holiday -

Caravanning has always been a working-class holiday that simply took them to the nearest seaside where they could get a little fresh air away from the cotton fibres; grease and heat of the industrial towns, presently many working-class and poorer families have never been to the seaside.

Yet the resurgence of this type of holiday has become the must-do thing for many of the middle classes, with caravans more expensive than many Northern homes.

This work is a reflection of the past and how people experienced the times back in the mills.

Through sight sound and smells the audience will experience the work within the context of what we assume is the working class today, with references to child labour, travellers, the homeless, and migrants. This work is about loss, the death of industry and towns.

“Weesh Thi Wurr Eer”